Earlier this month, I wrote an A1 story for the Post Register laying out the case against high school sports. As you can see above, the Post Register ran my sports con story next to a pro one written by another reporter. These two stories were inspired by a recent bond measure that proposed a new high school in Idaho Falls (it passed, and the new school will be built by 2018 or 2019).

Here’s the link to my story, with the full text below (the pro story can be found here).

When Bonneville Joint School District 93 looked for ways to trim the cost of its new high school bond, it didn’t consider eliminating one large money-sucker: sports.

The Nov. 3 bond dedicated $63.5 million to a new high school and its additions. About $15 million of that is going toward athletic facilities.

“If you did not have athletics, you’d have a lot of people not coming to your school,” District 93 superintendent Chuck Shackett said.

About 40 percent of Bonneville and Hillcrest high school students play sports, according to the schools’ athletic directors.

But are competitive high school sports, particularly football, a necessary component of a well-rounded educational experience?

A growing list of educational experts and medical doctors are arguing that they are not. Citing high costs for facilities, equipment and travel, distractions from academics and health concerns, they propose that removing sports from the school system would make students safer and more focused.

High costs

In its three attempts to pass the new high school bond, District 93 only considered removing an athletic cost once, when it separated the high school from the auditorium and football stadium on November’s ballot.

Both questions passed. As a result, several athletic facilities will grace the new school, which will have a 1,500-student capacity and will open in fall 2018 or 2019. Here’s the breakdown of the $15 million:

• $5.7 million for a competition gym

• $3.4 million for a practice gym

• $2.1 million for a football stadium

• $4 million for everything else (tennis courts, track, baseball, softball, soccer and physical education fields)

The stadium alone was not vital. The Highland, Pocatello and Century high school football teams all rent Holt Arena, which is also home to Idaho State University’s football team. Boise, Capital, Timberline and Borah all share the football stadium in Boise’s Dona Larsen Park. Three District 93 schools sharing one football stadium might be an inconvenience, but it wouldn’t be impossible.

But sports cost more than just the facilities to house them.

District 93 doled out $502,000 in athletic stipends to pay coaches, trainers, etc. for the 2014-15 school year while paying $156,700 in nonathletic stipends for department heads, club advisers, etc., according to district records. Those numbers are so disparate because the district has more athletic employees (coaches, trainers, etc.) than non-athletic (department heads, club advisers, etc.). Employees with more experience also receive larger stipends.

District 93 Chief Financial Officer April Burton said the district also funds transportation costs for all extracurricular

activities, which include organizations such as debate, band and orchestra.Distracting from academics

Idaho State University defensive lineman Tyler Kuder is set to graduate this month with a degree in sports management. When he attended Payette High School, he said all he cared about was playing sports and hanging out with friends. He earned a 2.4 GPA and a 20 on the ACT, causing several Division I football programs (including Boise State, Duke and Oregon) to lose interest in him.

“They didn’t have good academic support,” Kuder said of Payette.

High school is designed to educate teenagers and prepare them for adulthood. Yet, in many places across the nation, the students who participate in athletics are often pushed to excel on the field and merely get by in the classroom. In other cases, the students’ time is stretched so thin that they prioritize sports over studies.

“Sometimes, I got lazy thinking, ‘No, I’ve got football, I’ve gotta watch film,’ so I put that over homework,” Madison High School senior Michael Dredge said.

Student-athletes also frequently miss classes for travel to games and tournaments.

Bonneville High School athletic director Dale Gardner said freshman football players miss about one class a week, while baseball, softball, soccer and track athletes miss around four classes per week. Idaho Falls High School reported similar numbers. The number of missed classes increases if the athletes make district and state tournaments.

“Anytime any kid misses for any reason, whether they’re sick or whatever, that always puts an extra stress on the teacher because you still have to make sure that kid gets what they need,” said Natalie Woods, a math teacher at Hillcrest. “You hope that they’ll make good on themselves and come in and do it so you don’t have to chase them down.

“It’s just one of those things you deal with.”

Health concerns

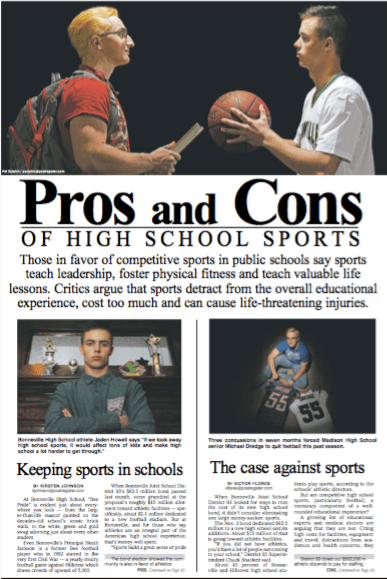

For the first time in his high school career, Dredge, a defensive lineman, didn’t suit up for the Madison football team this past season. Three concussions within seven months prompted his parents to put their feet down.

Dredge’s first two concussions came from wrestling, but the highest percentage of concussions in high school sports happen in football.

During the 2014-15 school year, 1,264 concussions were reported by Idaho’s high schools, according to a survey conducted by the Idaho High School Activities Association. Football accounted for 567, or 44.9 percent, of those concussions.

However, female athletes are not immune to concussions. Research by the Women’s Sports Foundation shows that girls playing in many high school sports have a higher incidence rate of sports-related concussions than males in similar sports.

“It’s a real issue that parents and administrators should be aware of,” Shackett said.

Dr. Bennet Omalu

wrote in a column published Monday in The New York Times that children should not be allowed to play high-impact sports until they are 18 years old. Omalu, a forensic pathologist, was the first to link head trauma suffered by football players to a neurological brain disorder, Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy.“The human brain becomes fully developed at about 18 to 25 years old. We should at least wait for our children to grow up, be provided with the information and education on the risk of play, and let them make their own decisions,” he wrote.

Additionally, 691 high school students have died from playing football since 1990, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research. At least eight have died this year, the Kansas City Star reports.

“No life is worth any sport,” Dredge said.

An alternative

Critics of school-based sports programs argue that eliminating competitive sports from public schools would allow the students and teachers to focus on the institution’s primary purpose: education.

In much of the world, high school sports do not exist. In Europe, teenagers who want to play competitive sports often participate on club teams outside school.

Former University of Nevada men’s basketball coach Len Stevens told the Reno Gazette-Journal in 2012 that adopting the European model would allow high schools to focus on academics and more inclusive athletic programs such as intramural sports and PE.

Other than school spirit, high school sports don’t have much more to offer than club sports. For example, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) is crucial for basketball players who want to play in college.

“The one thing about summer basketball is you get the chance to go see 1,000 kids at one venue on one day,” said Utah Valley University head men’s basketball coach Mark Pope, who signed former Bonneville player Telly Davenport last year. “It’s incredibly more efficient, in terms of a broad brush chance to evaluate, than it is to go visit kids at their high school.”

Clubs would not eliminate the danger of sports, but separating sports programs from the school system could reduce societal pressures on athletes to participate in competitive contact sports.

In their Oct. 30 paper titled “Medical Ethics and School Football,” published in the American Journal of Bioethics, Drs. Steven H. Miles

and Shailendra Prasawrote that “health professionals should call for ending public school tackle football programs.”“Private play and private leagues, like the Pop Warner program, would continue,” they wrote. “Young people choosing such programs would play purely for the game and not be lured by ‘school spirit.’”